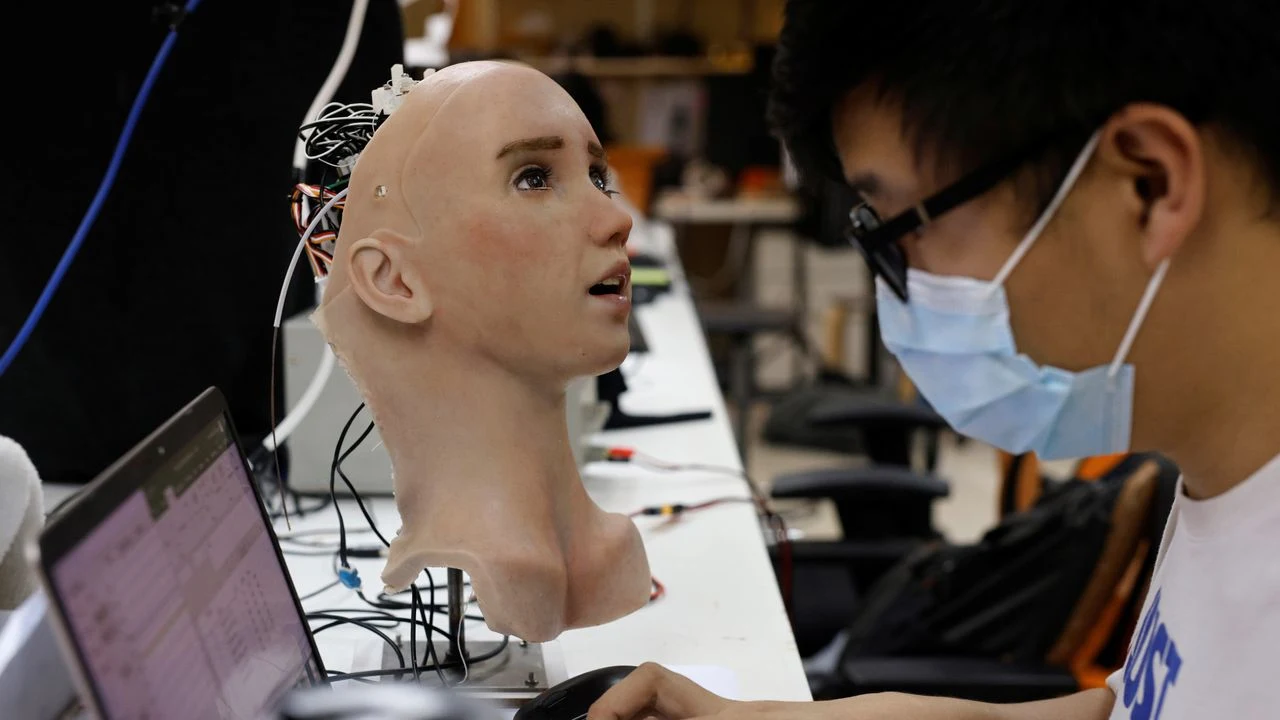

Chinese engineer working on a robotic project. For decades, China pursued a brand of centrally planned economic policies that the U.S. was h...

|

| Chinese engineer working on a robotic project. |

Beijing still uses five-year plans but now directs resources into basic scientific research with industrial applications. China’s foray into areas like artificial intelligence and robotics once dominated by the U.S. helps explain the Biden administration’s tilt toward industrial development policies, like spending government money to reassert competitiveness in semiconductor production.

“Decades of neglect and disinvestment,” President Biden lamented in June, “have left us at a competitive disadvantage as countries across the globe, like China, have poured money and focus into new technologies and industries, leaving us at real risk of being left behind.”

Beijing also emulates Washington by pouring government investment into its own versions of U.S. government research powerhouses such as the National Institutes of Health, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. “China aspires to be the first ‘government-steered market economy,’” University of California, San Diego, professor Barry Naughton writes in his newly published book, “The Rise of China’s Industrial Policy, 1978 to 2020.”

The late Chinese leader Mao Zedong’s first five-year economic plan in 1953 included the production of China’s first car, its first jet airplane and the first modern bridge over the Yangtze River, while the second plan launched in 1958, known as the Great Leap Forward, was a disastrously ill-conceived attempt to rapidly develop agriculture and steelmaking. The planning tradition outlived Mao.

For a long time China impressed Western politicians as the party’s centralized leadership plotted the future, telegraphing to officials, financiers and executives clear goals years in advance, helping lure hundreds of billions of dollars in foreign investment and becoming a manufacturing powerhouse. China’s industrial policy was focused on creating jobs and growth at home but benefited the international business. After the country entered the World Trade Organization in 2001, Beijing’s plans also included dismantling bureaucratic control of commercial activity.

Mr. Naughton dates the first inklings of a new tack to the period around the global financial crisis in 2008 when Beijing stepped up funding for megaprojects like a jetliner to compete with those made by Boeing and Airbus SE and its own homegrown version of the U.S. Defense Department’s Global Positioning System. After taking power in 2012, President Xi Jinping promoted a worldview of industrial and technological dominance as a political and security imperative.

Couched in terminology suggesting self-sufficiency goals, Chinese planning took aim at globalized sectors like car making by putting government money and regulation behind new concepts, like electrification. More recently, China has displayed expertise in more future-leaning areas such as quantum computing, challenging pacesetting Western nations. Mr. Naughton’s research finds that just one source of money for government priorities, “industrial guidance funds,” could have collected as much as $1.6 trillion in funding through mid-2020, mostly in the previous six years.

For Chinese scholars like Justin Yifu Lin, a Peking University professor who served as chief economist of the World Bank, China hasn’t changed its philosophy or approach and instead has all along focused on industries where it had a competitive advantage. Before the early 2000s, that meant that, effectively, “China wasn’t competing with the U.S.,” says Mr. Lin. “The change in perception is because you feel a threat,” he adds, addressing America directly. “In the past, you welcomed [development] because industrial upgrading contributed to the dynamic growth of China, and made the Chinese economy much larger for your industries. So you were happy.”

Columbia University economist Jeffrey Sachs says Beijing is investing in itself to advance technologically, as the U.S. has done, and concerns by American politicians that this is unfair are “hugely overblown, inaccurate, naive, and unprincipled.” Today, 38% of multinationals say their China operations are being negatively affected by Beijing’s industrial policies, according to a membership survey by the U.S.-China Business Council published in August, more than three times the proportion two years earlier.

Political thinkers in Beijing are preparing their defense by dusting off “Entrepreneurial State,” a 2013 book by Italian economist Mariana Mazzucato. It argued U.S. government-led innovation has been the key change agent for American private industry; for instance how GPS helped make Apple iPhone a truly smart device. “That’s not communism. That’s exactly what the U.S. did,” she said in an interview. China’s government-funded programs will take years to prove their worth.

“Whether or not the industrial policies that have been followed in the most recent decade will contribute to China’s technological and economic prowess is not yet clear,” says Mr. Naughton’s book. Still, Washington is consumed with beating China. The U.S. faces decisions about whether it is worth putting government money into innovations that might fail, said Christopher Johnson, a former U.S. intelligence analyst and president of Washington risk advisory China Strategies Group. “The Chinese have decided it’s worth it.”