Research uncovers possible monoclonal antibody treatment for Lassa fever. Lassa virus is a single-stranded RNA virus belonging to the Arenav...

Lassa virus is a single-stranded RNA virus belonging to the Arenaviridae family, and it is the causative agent of Lassa fever, a viral hemorrhagic fever. This virus is primarily found in West Africa, particularly in countries such as Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Guinea.

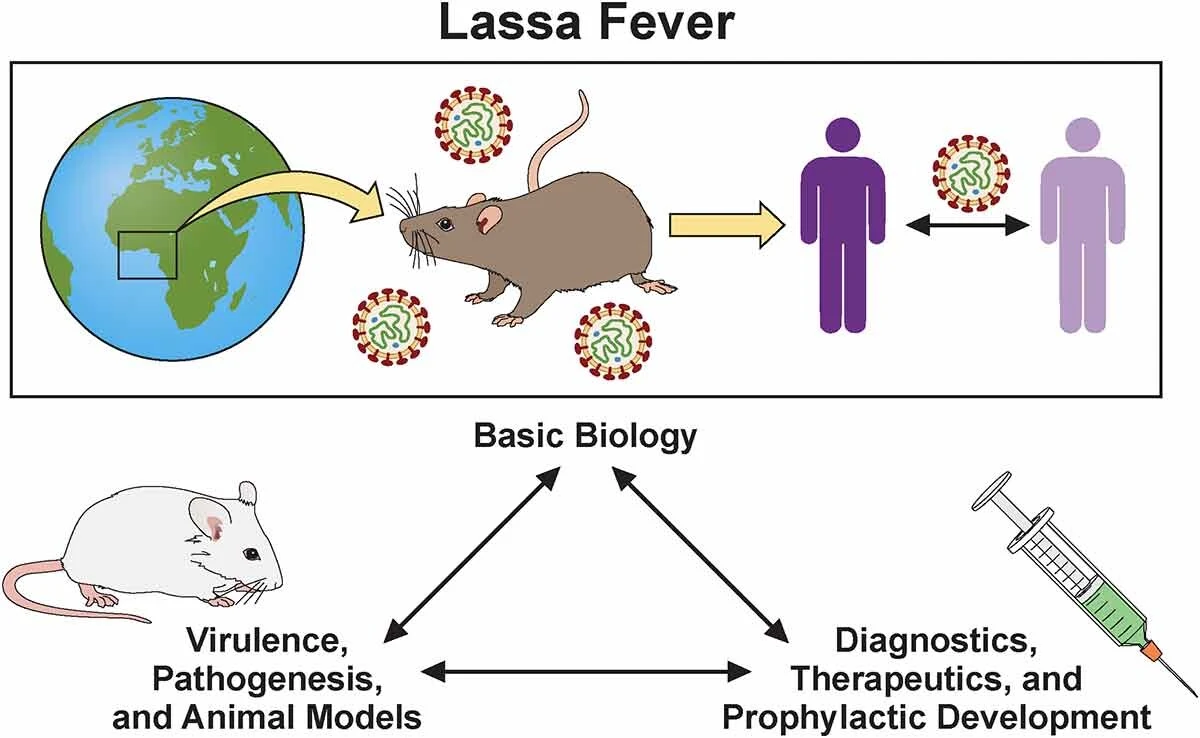

Lassa fever is transmitted to humans through contact with infected rodents, particularly multimammate rats of the genus Mastomys, or through exposure to bodily fluids of infected individuals. The disease can range from mild symptoms to severe hemorrhagic fever, with approximately 1% of cases resulting in death. Lassa fever is a significant public health concern in West Africa, and efforts to control the spread of the virus include surveillance, early detection, and appropriate medical treatment.

|

| The disease can range from mild symptoms to severe hemorrhagic fever. |

"Much of the value of our work was in learning more about — and overcoming — the many practical obstacles to performing a [genome-wide association study] of this nature in a developing country," co-first author Siddharth Raju, a graduate student in Pardis Sabeti's lab at Harvard and the Broad Institute, said in an email. He noted a range of challenges the team faced along the way, from small sample sizes and uncertainty in defining cases and controls to environmental factors and an incomplete understanding of the genetic diversity found in African populations.

While the hemorrhagic form of LASV infection has an estimated fatality rate approaching 30 percent, the team explained, a subset of infections is marked by mild or negligible symptoms. To tease out genetic factors that might contribute to this wide range of LASV infection outcomes, in particular those associated with fatal Lassa fever, the investigators brought together array-based genotyping data for 533 Lassa fever cases in Nigeria and Sierra Leone and 1,986 control individuals from the same populations.

|

| Pathogenicity and virulence mechanisms of Lassa virus. |

While the investigators did not detect variants linked to overall LASV susceptibility in their GWAS, they did find significant associations for fatal Lassa fever outcomes at sites in the GRM7 gene and downstream of the LIF gene in the Nigerian cohort, and in a subsequent meta-analysis that included LASV cases and controls from both Nigeria and Sierra Leone.

Along with additional analyses on viral sequences and sequences from the host human leukocyte antigen (HLA) region in a subset of participants, the researchers took a closer look at a long-range haplotype on chromosome 22 that was previously found to be under positive selection in Nigeria. The haplotype surrounds a gene called LARGE1, which codes for a protein that glycosylates the cellular receptor that LASV uses to enter host cells.

Past research has shown that LARGE1 expression influences the infectivity of LASV in in vitro experiments, and the authors speculated that "a variant in the putative region under positive selection may have been driven to high allele frequencies by impacting expression levels of LARGE1, thereby reducing the risk of severe Lassa fever."

To explore potential ties between the haplotype and LASV susceptibility, the team performed additional association, haplotype frequency, and massively parallel reporter assay-based variant analyses.

In the process, Raju explained, the investigators showed that the LARGE1 haplotype, which includes variants in linkage disequilibrium over 500 kilobases, was significantly associated with Lassa fever susceptibility in the Nigerian cohort, but not in the cohort from Sierra Leone.

Though the haplotype is overrepresented in populations where LASV is endemic and lacking in Asian or European populations, he cautioned that further research will be needed to shore up the proposed ties between LARGE1 selection and Lassa fever, particularly since the association described in the current study was "driven almost entirely by individuals recruited early on in our study." "Ultimately, larger collections and deeper phenotypic characterization will be required to adjudicate the hypothesis of LARGE1-mediated genetic resistance to Lassa fever susceptibility," Raju said.

More broadly, he and his coauthors suggested that the continuing efforts to improve our understanding of genetic variation in African populations will allow further insights into potential links between genetics and disease," while "metagenomic sequencing could define the genome of the infecting LASV strain while identifying the presence of co-infections, allowing these factors to be accounted for in the association model."